With all the discussion and public discourse surrounding immigration, we thought a discussion on where the intersection of immigration and capitalism exists would be appropriate.

Before we walk down this path, I want to stress that the ideas and concepts I am presenting are not exclusively mine, rather these are the implications from widely recognized and respected economic models.

We are going to deduce the essence of these models and reconcile them with immigration, as a whole.

In terms of classic economic models, few to none actually deal with the movement of people under the umbrellas of immigration or illegal immigration. This is because economics as a whole does not concern their modeling with qualitative aspects of workers; this tenet of economics results little attention paid to issues such as nation of origin or even the larger concept of citizenship.

While contemporary economic modeling has begun to explore such issues, the foundational models do not. Some of the most important models in the history of economics only account for one or two variables.

Since immigration is a labor issue, we are going to cover the models from their implications on labor and wages.

Let us begin with first step in the immigration and capitalism path, the Lewis Model. The Lewis Model, sometimes referred to as the Dual-Sector Model, is from the great mind of Nobel Laureate W. Arthur Lewis; the only person of African descent to win the Nobel Prize in Economics. This model is truly the origin to our journey.

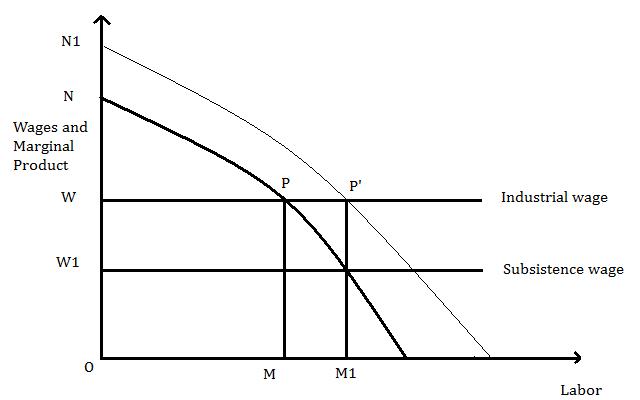

The Lewis Model explains to us how economies convert from subsistence economies to capitalist economies. The model can be broken down to one theme, the less friction between the transition to capitalism from subsistence economies the greater the benefit. Now, the interesting aspect of this model is that government intervention on either side (subsistence or capitalism) leads to a theoretical inefficiency.

The Lewis model shows us that prohibiting immigration slows down the progression, or intensification in economic lingo, of economies in their early stages. In short, the Lewis model show us that as long as there is demand for labor in the capitalist sector, immigration is needed to feed growth; without immigration there is no development of capitalism in developing economies.

To progress further, we have to jump to another pillar model in developmental and labor economics to the Harris-Todaro Model.

While the H-T Model (as it is referred to in most discussions) does not have the hardware the older Lewis Model does, it is one of the most influential models ever produced and the journal article that the model appeared in was named one of the top twenty articles published in the first hundred year of the American Economic Review (the most prestigious journal in the field of economics).

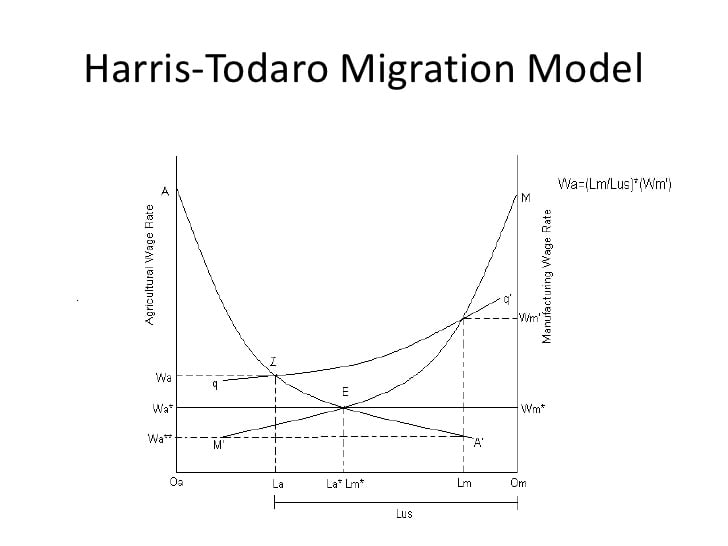

Now that I have hopefully convinced you that the H-T model is worth listening too, let’s break it down. The H-T model looks at the step after the Lewis Model. While the Lewis Model covered the transition from a subsistence economy to capitalistic economy, the H-T Model covers the intensification that occurs with-in capitalistic economies from a sector standpoint.

The H-T Model examines the transition of workers between rural areas and urban areas, but “rural” and “urban” could be better understood as agricultural work and manufacturing work, respectively. While this model offers us a wide array of insight into such concepts as urban economics, geospatial economics, and developmental economics, we are concentrating on the implication the model has on the field of labor economics.

In regards to immigration, the H-T Model shows that if unrestricted immigration from the rural sector to the urban is allowed, as long as labor demands are not exhausted, there should be an increase in wages for all in the urban sector. In a more general sense, unrestricted immigration between non-developed areas and developed areas results in the net receiving sector increasing wages for all in that sector. Conversely, if the immigration to the urban sector exhausts the labor demand, the Model demonstrates (and we see it in places like Rio de Janeiro, Brazil) that slums will appear on the outskirts of the urban sector.

The slums form because individuals behave in their best interests; the allure of the higher wages in urban sector attracts laborers who are willing to take a chance of being destitute to secure a higher wages. The key take away from the H-T Model, regarding immigration, is as long as there is a surplus demand in labor, immigration leads to broad increases in wages in developed economies.

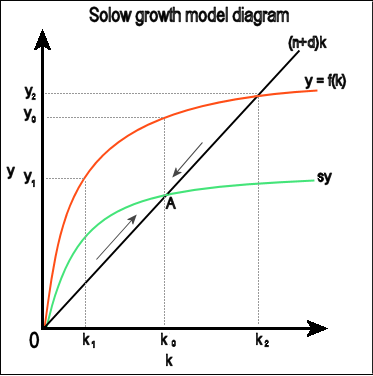

These two foundational models lead us to the most widely accepted and crucial model for understanding economic growth, the Solow Growth Model. Developed by Nobel Laureate Robert Solow, and independently by Trevor Swan, in the mid-1950s, the Solow growth Model is arguably the single most influential model in modern economics. The model boils down to one basic proof, economies grow when they accumulate capital faster than the capital they have depreciates.

But wait a minute, why aren’t we talking about labor?

We are, but economies are the result of two inputs: labor and capital. The more efficient either is used, the greater the economic growth. Capital becomes more efficient as laborers with higher productivity enter the economy. If immigration to developed areas results in increased productivity in the labor sector, which is shown to be true in the H-T Model, then capital accumulation is increased. This increase results in increased economic growth. The Solow Growth Model shows that the ability to increase capital accumulation is paramount to economic growth. Immigration plays a large role in increasing the efficiency of capital.

While economic models are inherently theoretical, the journey and conclusions we just walked through have a real life example.

Under President Kennedy, illegal immigrants of Mexican descent were targeted for deportation under the pretense that the immigrants were suppressing wages in the low skill field of agricultural harvesting, along with stealing jobs from Americans. The end result of deporting the illegal immigrants was cross market wage reduction of all workers still remaining in the industry and a massive labor supply shortage. Interestingly, this is one of the few examples where a labor shortage causes wages to fall; this is due to firms being unable to reach a profitable output (remember there were not enough people to pick all the produce) in order to stay solvent, the firms have to cut wages.

The most prominent classical and neo-classical economic models paint immigration (the models do not distinguish between legal and illegal immigration) as both the necessary precursor for capitalism and vital to the continued expansion of capitalistic economies.

Government interference in markets virtually always involves introducing inefficiencies.

The question to ask oneself when it comes to immigration and government is, are the perceived pros produced by restricting immigration worth the inefficiencies generated?

RELATED:

• Income Inequality: A Simple Case of Supply and Demand

• #DeleteUber Trends Amid Refugee Ban

• Trump Takes Action on Trade: Pulls US Out of TPP, To Renegotiate NAFTA