The Falsehood of the Unemployment Rate and the Effects of Expanded Unemployment Programs

The U.S. Civilian Unemployment Rate has fallen back to pre-recession level. That’s good, right?

Not quite.

The unemployment rate is the number of people unemployed, or people looking for a job who currently do not have one, divided by the labor force. The labor force is the entire population of people who are employed and people who are unemployed.

If we divided the labor force by the total population of the United States, we derive one of the most important statistics in all of labor economics; Labor Force Participation Rate.

Why is labor force participation so important? The labor force participation rate gives the unemployment rate perspective; let’s walk through an example.

Let’s break down the U.S. economy into 100 people.

Before the recession, of those 100 people, 66 where in the labor force and three were unemployed.

In today’s 100-person U.S. economy, 62 are in the labor force and three are unemployed.

Both scenarios had the same unemployment rate, but different labor force participation rates, and thus different economies.

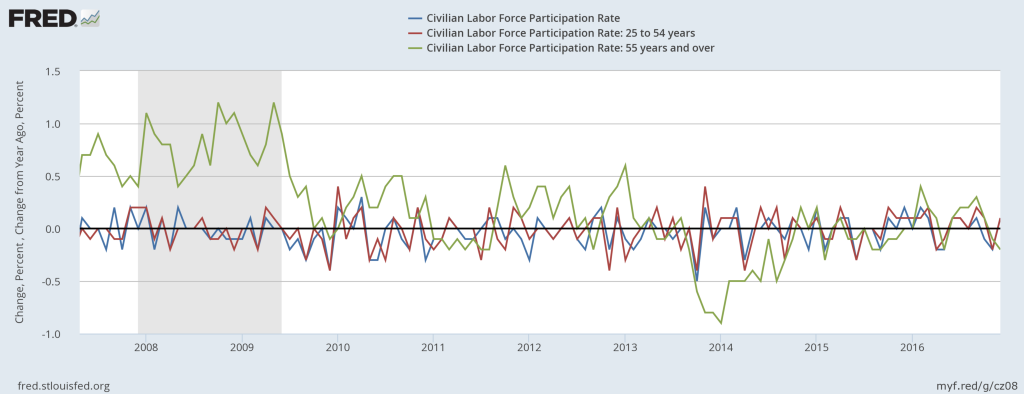

The current unemployment rate is the exact same as the unemployment rate just before the recession, but the labor force participation rate has never recovered since the recession. Before the recession, the participation rate was 66.2 percent. The most recent U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics data shows a participation of 62.7 percent.

More importantly, the rate has been fairly stagnant since 2014. While the unemployment rate has recovered, the labor market hasn’t.

Politicians tout their economic success on lowering the unemployment rate, but if people have become so discouraged by their job perspective that they rather engage in social welfare programs than look for employment opportunities, is that really something to hang a hat on?

This is what the econometrical evidence points to. From a labor economic standpoint, the economy has not recovered from the recession. The low unemployment rate is meaningless when it is the product of people giving up on ever finding gainful employment.

The decrease in the labor force participation rate is the product of multiple factors, but none is more directly related to government intervention than the expansion of unemployment insurance.

The extension of unemployment benefits to 99 weeks in 2009 under the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act triggered a serious negative externality.

Historically, the larger the displacement in time between jobs, the less likely an individual will be able to find a job with a comparable wage of their previous job.

By incentivizing the ability to delay acquiring a job, the federal government partially caused a retraction in the amount of people participating in the economy. Furthermore, as the U.S. economy intensifies, technology is becoming more and more ingrained into every occupation.

The longer the unemployment period, the more technological skills deteriorate. This decline is caused by the skill atrophy experienced when workers are not frequently using necessary operational programs.

The amount of time a worker is out of the workforce is directly correlated to deterioration of their ability to efficiently use technology.

The end result of this chain reaction is companies having to spend more money training employees to get them current with industry standards, or workers having to take on student debt to train themselves to re-enter the workforce, both great hurdles to sustainable employment.

While the average person deals with technologies, they do not deal with industrial systems regularly. The ability to extend the period of unemployment, along with the ever-accelerating pace of technological advancements, resulted in a drastically different market in which firms are spending more money to train people.

This increased need to train employees hurts older workers more than any other demographic.

Firms see training investments in twilight stage employees as having a far lower return rate than in younger employees. Additionally, younger employees are less costly to train on technology than older employees.

This causes a chain reaction whereby baby boomers are retiring earlier and taking a drastically reduced Social Security payout. Early Social Security payment schedules, coupled with fewer years paying into retirement plans, creates a financial cocktail of perpetual borderline poverty and intergenerational financial dependence—parents relying on their children for financial support.

The reduced wages further incentivize the transition to public social program, rather than gainful employment. This process is demonstrated by the lowered and stagnant post-recession labor force participation rate.

While the expansion of unemployment benefits was seen as a way for the federal government to lessen the impact of the recession, the actual result was suppression of the labor force that we are still observing a decade after the beginning of the recession.

Labor markets are incredibly sensitive to changes in policies, technology and laws. If the federal government looked to minimize its involvement in the labor market correction after the recession, we may not be seeing such low participation in the labor force today.

The unemployment rate has fallen, but the reality is that the practical implications are drastically dampened by a dramatic reduction in overall level of worker in the U.S. economy. We will be fully recovered from the recession when the labor force participation rate, not the unemployment rate, returns to pre-recessions levels.

RELATED:

• Retiring Baby Boomers Only Half the Problem of Declining Labor Force

• Income Inequality: A Simple Case of Supply and Demand

• Automation Won’t Take Your Job If You Take Responsibility For Your Destiny